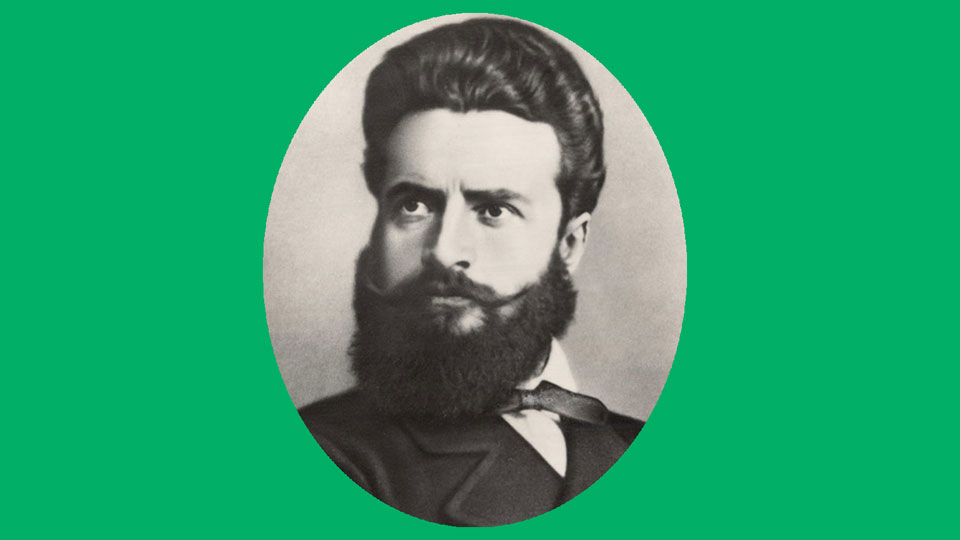

Hristo Botev (BG: Христо Ботев) was a Bulgarian poet, revolutionary and national hero. He is widely considered the leading voice of the Bulgarian National Revival and, alongside Vasil Levski, is remembered as one of the two greatest patriots in modern Bulgarian history.

Who was Hristo Botev?

He was born Hristo Botyov Petrov on 6 January 1848 in Kalofer, Bulgaria, the first of nine children born to Botyo Petkov (1815–1869) and Ivanka Boteva (1823-1911). His father was the local school teacher, an important figure in the Bulgarian National Revival and a significant influence in the life of the young Botev.

Hristo Botev received his early education under his father in Kalofer and Karlovo.

Botev’s Odessa Sojourn

In 1863, after completing his basic education in Kalofer, Botev’s father sent him to high school in Odessa, Ukraine. There he discovered the Russian poets of his day whose works inspired in him revolutionary thoughts, and he began writing poetry himself.

While in Odessa, Botev developed a relationship with the Odessa Bulgarian Board (BG: Одеско българско настоятелство), an association of Bulgarian immigrants committed to Bulgarian education and the Bulgarian national revival.

Botev entered the Second High School in Odessa as an auditing student, because he was not well enough prepared to enroll as a regular student. He had a difficult time there, often complaining of the discipline enforced in the school. Restless and unruly, he left the student boarding house in 1864 and started living on his own.

Despite letters of instruction from his father and advice from his father’s friends, he became estranged from the Odessa Bulgarian community and they distanced themselves from him.

In 1865 he was expelled for negligence when it became clear that he was unable to advance to third year studies. His stipend was canceled. He was given a small sum to return home, but instead of leaving he remained in Odessa, growing closer to the Polish community. He supported himself by offering private lessons and enrolled as an auditing student in the Philology Department of the Imperial New Russian University (today Odessa University).

In September 1866, Botev took up a teaching position in Zadunaevo, a Bulgarian village in the Russian part of South Bessarabia. After just a few months he received notice that his father was seriously ill , and decided to return home. He sailed by ship, probably from Odessa to Burgas, and arrived home in Kalofer at the beginning of April 1867.

Hristo Botev’s Return to Kalofer

With his father ill, Botev quickly took his father’s place teaching in the local school.

About that time, on 15 April, Botev’s poem Майце си (You are a Boy) appeared in Гайда, Petko Slaveikov’s periodical published in Constantinople. It was Botev’s first published work, but, since it appeared without attribution, many of his acquaintances failed to recognize his work.

On 11 May, during the celebration of Saints Cyril and Methodius Day, Botev delivered an improvised speech criticizing the moderate stance of the national liberation movement, which at that time was focused on the creation of an independent Bulgarian church. His words provoked the specter of retaliatory actions by police, but in the end nothing came of the situation.

When Botev’s father recovered in the summer of 1867 he returned to his teaching duties and appealed to his friends on behalf of his son. He successfully raised a stipend and sent Hristo back to Odessa to complete his education.

Hristo Botev in Romania

Instead of traveling from Kalofer to Istanbul and then on to Odessa, Hristo Botev detoured to Romania, stopping briefly in Giurgiu, an administrative town opposite Ruse on the north bank of the Danube river. There he fell in with Hadji Dimitar and other Bulgarian revolutionaries.

About that same time the well known Bulgarian writer and revolutionary Georgi Rakovski died in Bucharest, and Botev traveled there with the rest of the Bulgarians for the funeral. This depleted his funds. The Bucharest based Bulgarian political organization Virtuous Fellowship (Добродетелна дружина) came to his rescue, providing financial assistance for him to continue his journey.

Botev left for Odessa, but only got as far as Braila, another Romanian port town farther down the Danube. It is unclear why he stopped there rather than continuing on to Odessa, but apparently he complained later that local Bulgarians reneged on a promised scholarship to study in Prague. Whatever the case, he stayed in Braila, finding an outlet for his writing in Dimitar Panichkov’s Danube Town newspaper. Botev’s second published work, “To His Brother,” appeared in its pages in January 1868, along with an unrealized promise to publish later a whole volume of prose and verse.

Many Bulgarian revolutionaries gathered in Braila at the beginning of 1868, planning to send detachments to Bulgaria that summer. Hristo Botev enlisted in that of Zhelyu Voivoda, for which he was appointed clerk.

Botev passed the spring acting in theatrical productions put on by the famous playwright Dobri Voynikov. After brawlng with turks in the city park, Botev went into hiding at Panichkov’s printing house. In June he traveled with Zhelyu Voivoda to Odessa in search of funding for their detachment, but upon their return Voivoda was detained by police and their summer expeditionary plans evaporated.

In September 1868, Botev joined Dobri Voynikov’s amateur theater troupe when it traveled to Bucharest. He tried to find work there as a teacher, but failed due to his poor command of the Romanian language. He enrolled briefly in the Bucharest Medical School, but stayed only a few weeks. In the end he decided to return to Bulgaria.

Once again lacking funds for the journey, he remained in Romania. For a time he lived with Vasil Levski in an abandoned windmill. In a letter to his friend Kiro Tuleshkov, he shared a somewhat incredulous impression of the Apostle:

“My friend Levski, with whom I live, is an impossible character! Even when we find ourselves in the most dire straits, he is as cheerful as if we are in the best of circumstances. Cold, wood and stone creaking, hungry for two or three days, yet he sings and makes merry! Evening, as we lay in bed, he sings; morning, when his eyes open, again he sings!”

In January1869 he received permission from the Romanian Ministry of Education to establish a Bulgarian school in Bucharest, but was unable to find funding for the project. The next month, with help from Hristo Georgiev, Botev was appointed a Bulgarian language teacher in Alexandria, southwest of Bucharest. That position didn’t last long. He was fired after coming into conflict with wealthy Bulgarians from the city, whom he accused of lack of patriotism. He remained in Alexandria until August, when he was appointed a teacher in the town of Izmail in Romanian Bessarabia. At that time Botev’s father died in Kalofer, leaving his large family with limited resources.

In Izmail, Botev taught Bulgarian language in the Romanian public school. While there, he collaborated with several Bulgarian newspapers in Bucharest, including the satirical Drum (BG: Тъпан) and Lyuben Karavelov’s Freedom (BG: Свобода), where in the summer of 1870 he published edited versions of Your T-Shirt and To Your Brother, as well as new poems Elegy and Division, which was dedicated to Karavelov. All the while Botev maintained contact with illegal organizations of Russian political emigrants and suffered from recurrent bouts of malaria.

In the spring of 1871, the municipality of Izmail decided to stop offering Bulgarian language in the public school and suspended Hristo Botev’s salary. According to Kiro Tuleshkov, this happened on the eve of Saints Cyril and Methodius Day after Botev absconded with money collected to celebrate the holiday.

After a short stay in Galati, at the end of May 1871 Hristo Botev moved to Braila. Here, with the assistance of Dimitar Panichkov, he began publishing the newspaper Duma na bulgarskite emigranti, which was to replace the previously closed Bulgarian emigrant newspapers Svoboda and Dunavska Zora. The newspaper is published in only five issues, and the main part of their content is written by Botev himself. They publish some of his main journalistic works: “Instead of a Program”, “Examples from Turkish Justice”, “The People – Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”, “Funny Cry”, “Petroshan”, “Is the Church Question Resolved?”. In Duma, for the first time, several of his poems were published – “To my first libe”, dedicated to Maria Goranova “Pristanala” and dedicated to her brother B. Goranov “Borba”. [26]

In the summer of 1871 Botev became seriously ill for a long time with typhus, and at the end of July he and Panichkov were forced to stop publishing Duma due to lack of funds. In September he published a pamphlet with sharp attacks against the Bulgarian Literary Society (now the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences) and personally against its clerk Vasil Stoyanov. They were repeated a month later at the annual meeting of the Society, where Botev and Dobri Voynikov attended as delegates of the Bulgarian municipality in Galati. [27]

Information about the life of Hristo Botev at the end of 1871 and the first half of 1872 is scarce. At that time he maintained active contacts with Russian socialists, such as Nikolai Meletin and Sonia Rubinstein, sister of the famous pianist Anton Rubinstein. At the end of 1871, Botev and Meletin tried to blackmail a wealthy Braille Bulgarian for money, but were discovered by the police and left for Galati. In Galati, the two, along with other accomplices, robbed several merchants and even tried to counterfeit money. [28]

At that time, in February 1872, Botev published the poem “Stranger” in “Svoboda”. In the spring, on the denunciation of the Russian consul in Galati, Meletin was arrested, and in April Hristo Botev. Russian anarchist literature was found in his home, he was accused of spreading radical political ideas and was sent to Focsani prison. He remained there for several months, after which he was released and in July or August 1872 arrived in Bucharest. According to Kiro Tuleshkov, the release from prison took place after a written guarantee from Lyuben Karavelov and Dimitar Tsenovich, sent at the insistence of Vasil Levski. [29]

In Bucharest, Botev settled in a room in the attic of Karavelov’s printing house, where he lived with Kiro Tuleshkov. He began working as a proofreader for Karavelov’s newspaper Svoboda, later renamed Nezavisimost, and in the spring of 1873 he directed the publication of Karavelov’s satirical newspaper Budilnik. It features some of his famous feuilletons, such as “O, tempora! Oh, mores! ”And“ This is waiting for you! ”, As well as the poems“ Why am I not …? ”,“ St. George’s Day ”and“ Patriot ”. During this period he translated a Russian textbook on arithmetic, but inserted political comments in it, and the book was destroyed after it was printed in Plovdiv. [30]

In the second half of 1873 Hristo Botev published in “Independence” some of his most famous poems: “Hadji Dimitar” (August 11, on the occasion of the fifth anniversary of the death of Hadji Dimitar), “In the tavern”, “My prayer” and “A dark cloud came.” After November 1873, Botev did not publish new poetry for nearly two years. At that time, by order of Karavelov, Botev translated the book “The Eastern Question and Bulgaria” by the officer from the Russian secret services Ivan Liprandi. Towards the end of the year, he appears to be taking his younger brother Stefan with him. [31]

In the spring of 1874 Botev got a job as a teacher in the Bulgarian school in Bucharest. It is housed in part of the home of the local Bulgarian bishop Panaret Rashev and Botev goes to live there, leaving Karavelov’s printing house. There he met his future wife Veneta Vezireva, the bishop’s niece. Despite numerous testimonies of personal conflicts with Karavelov, even after his appointment as a teacher, Botev continued to actively collaborate with the Nezavisimost newspaper, where his articles and feuilletons began to appear. [32]

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.