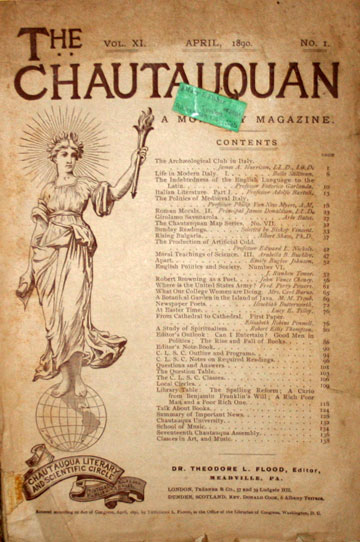

Shaw, Albert. “Bulgaria Rising.” The Chautauquan 11.1 (1890): 37-42.

About the author

Albert Shaw was an American academic and journalist best known for his work as the longtime editor-in-chief of the American Review of Reviews (1891-1937). He was an expert in municipal government and a close associate of Teddy Roosevelt. He wrote several articles about Bulgaria after traveling in Europe in 1888.

For ten years the eyes of Europe have been turned upon Bulgaria. Just emerged from centuries of Turkish rule, these people so long reputed a dull, stolid subject race have been touched as by magic with the spirit of progress. Their sudden development of capacity and of high aspiration has won the enthusiastic admiration of discriminating men, and has forced the respect of great powers and small powers alike.

For ten years the eyes of Europe have been turned upon Bulgaria. Just emerged from centuries of Turkish rule, these people so long reputed a dull, stolid subject race have been touched as by magic with the spirit of progress. Their sudden development of capacity and of high aspiration has won the enthusiastic admiration of discriminating men, and has forced the respect of great powers and small powers alike.

The burning center of European politics is so remote from our country, and a clear knowledge of the Balkan states and their conditions is so unusual among us, that we have come short of a full recognition of the claims that Bulgaria possesses to our friendship and sympathy. The Bulgarians have seemed to lack those qualities that in times past have won for the Poles or the Hungarians the keen sympathy of intelligent and imaginative people everywhere. Simply a subject Christian race in European Turkey, ethnologically Finnish, in language Slavonic, living in agricultural village groups, working gloomily and patiently, yielding to the exactions of the Turkish tax-gatherers, Christians in name but with strange infusions of Mohammedanism and of Persian paganism, more Asiatic than European, with almost no literary fragments, and with an inferior stock of national songs, traditions, and folklore, — such were the Bulgarians as the world knew them fifteen years ago. Their towns were squalid Asiatic villages. Their farming was that of the primitive period when these and the other tribes of Central and Eastern Europe came from Asiatic highlands.

How were new life and hope kindled in the Bulgarian spirit? Probably Russia is to be credited with the principal influence. Russian development has been very rapid. The religious enthusiasm of Russia began to be aroused for kindred peoples, of the same faith and of similar speech, who were under the domination of the Turk. Russia had begun to press against the Mohammedans in Asia, was sending thousands of pilgrims yearly to the Holy Sepulcher and the Jordan, was developing the spirit of a new crusade, and had fairly conceived of the struggle as lying between the holy orthodox Greek Church led by Russia, And the Mohammedan faith as sustained by the Turkish Empire. Naturally the Russians became possessed of the idea that it was their mission to aid their brethren of the European Turkish provinces, and eventually to drive the Turks out of Europe. Thus they already had secured for Servia a position of semi-independence in the empire; and they began now to send their agents and emissaries, religious and political, into Bulgaria. The so-called Pan-Slavist agitation began in earnest. The Bulgarians grew less patient under the yoke. Their priests became Bulgarian patriots.

A less aggressive, but perhaps not less deeply potential, influence stirred the Bulgarian nationality from an entirely different quarter. As the result of American missionary enterprise, Robert College had been founded upon the Bosphorus near Constantinople. The largest element among its students was Bulgarian. These boys learned the English language, learned modern history, found out, to their astonishment and grief, how deeply sunk their own people were, and went back to Bulgaria with a spirit that I can compare to nothing else than that which we have called “the spirit of ’76.” Broad-minded, great-hearted Americans, descendants of the fathers of this republic, were the teachers of these Bulgarian boys, and they inspired in them a courage and a manliness, the subsequent growths and achievements of which have astonished the world. They found their pupils a sturdy stock, with powers of endurance and steady application, and with a capacity for the highest and best things, — strong especially in their moral natures and in virile spirit. These boys, taught by Americans on the Bosphorus, were destined to play a great part in the emancipation and development of Bulgaria.

It was through Robert College and its pupils Mr. Gladstone and the English liberals learned the truth about the frightful massacres and atrocities perpetrated among the Bulgarians by the Turks in 1876. Their speeches so powerfully affected English sentiment as for the time being to change the traditional policy of Great Britain as the defender of Turkey, and to permit Russia to march first across the Danube, then across the Balkans, and finally to the sea at the very gates of Constantinople. The terrible war of 1877 had placed Turkey wholly at Russia’s mercy. The Treaty of San Stefano, at the end of the war, besides making great concessions of territory to Russia in Asia, carved out of the heart of European Turkey a Bulgaria so large as to leave only a narrow wedge-like strip running west from Constantinople as Turkish soil. The new Bulgaria was to be a self-governing principality. It included Bulgaria proper, East Roumelia, and most of Macedonia, — all the region actually inhabited by Bulgarian people. But the great powers refused to accede to the treaty Russia and Turkey had made, and the Congress of Berlin in 1878 apportioned the Balkan as it pleased. Roumania was made an independent kingdom. Servia was allowed to assume the same rank. Bulgaria proper was made an autonomous principality, paying tribute to the Porte and governed by a prince who should be agreed upon by the Powers and the Porte. South Bulgaria was called East Roumelia, and was kept much more closely attached to the government of Turkey. Macedonia was left a Turkish province.

The arrangement was disappointing and unjust, but it had to be endured. The Bulgarians at this time were full of gratitude and good-will towards the Russians. Their little country was almost covered with the graves of Russian soldiers who had died for Bulgarian freedom. The printed portraits of the Czar were in every Bulgarian cottage. The young Bulgarian army was in the hands of Russian officers. The new principality bade fair to be an obedient vassal of the great northern power, an ally and a ground of vantage in the next great struggle that was to involve Europe and in which Russia was to contend for the prize of Constantinople, the hegemony of the entire Balkan peninsula, and the autocracy of Asia minor.

A liberal constitution was given the new country, and a manly young prince, Alexander of Hesse Darmstadt, was sent to rule over it. When he came to the throne of the principality, in 1879, he was twenty-three years old. He was a nephew of the Czar of Russia, and his policy was at first almost that of a Russian pro-consul. But the national aspirations of Bulgaria grew fast; and the dictatorial treatment of Russian political agents and military men became intolerable. They interfered in the elections, and made themselves obnoxious beyond all comprehension. Alexander found it impossible to serve Russia and Bulgaria at the same time, and so he became a Bulgarian with all his heart. His difficulties waxed very great after the assassination of the Czar in 1881. The new Czar proved to be his inveterate enemy. Russia, with an arbitrary government, and with designs upon the countries lying southward, could not tolerate the growth of real freedom and independence in the Balkan States. Disagreement was inevitable. There never was a more disgraceful chapter of plots and intrigues than is the detailed record of the behavior of the Russian emissaries in Bulgaria between 1880 and 1886.

In 1885, there broke out in Philippopolis, the chief town of East Roumelia, a sudden revolution against the Turks. This province is directly south of Bulgaria, and is separated from it by the lofty Balkans. Its people are Bulgarians, and the revolution had as its aim the political union of “the two Bulgaries.” Alexander had not instigated the outbreak. It was a genuine movement of the people, justified by all of the moral facts of the situation, and appropriate from every honorable point of view. There was no railroad at that time, and Alexander drove in a droschka day and night till he reached Philippopolis. He put himself at the head of affairs, brought order out of anarchy in a single day, and effected a union of the provinces that was afterward embodied in the constitutional arrangements. Urged to take the step by jealousy and by Austrian instigation, King Milan of Servia now invaded Bulgaria with an army of 200,000 men, claiming that the union of the provinces had disturbed the balance of power in the Balkans and that it endangered the future of the Servians. It was an unneighborly, a wicked act. The Bulgarian army was small, but determined; and Alexander proved a rare leader. The Servians were routed in a severe battle, pursued, and beaten again on their own soil, and only saved from severer consequences by the threats of Austria and Russia, which were preparing to invade the country from opposite sides. Alexander was now a hero with the Bulgarians. He was magnanimous with the pro-Russian plotters, and enthusiastic in his plans for the progress of the country that had so warmly adopted him. Modern times have not seen a braver or better prince. But he could not stand against the enmity of his powerful neighbors. A perfidious plot in 1886 resulted in his kidnapping and the seizure of the government by his enemies. He was carried to Russia, and he made his way thence to his early home. But the people of both Bulgarian provinces, with the army at their back, demanded his return. He obeyed their wish, and received ovations such as are accorded to few men. But the situation seemed to him untenable. The Czar, his cousin, would not relax his hostility. Alexander, therefore, abdicated, and the government fell into the hands of a regency. The treatment of Alexander by the European powers was a cruel blow to a brave young people who asked nothing but to be let alone, and a personal outrage against one of the most gallant and popular leaders who ever worked in a pure and patriotic cause.

Alexander could not see his way clear to resume the government without the assurance of support from the great powers. The regency governed in the name and in the interest of Bulgaria, and meanwhile a new prince was found. In the summer of 1887, Ferdinand, the young Duke of Saxony, then twenty-six years old, was unanimously elected by the Bulgarian National Assembly, and in August he assumed the government. This action, which, according to the treaty of Berlin, should have had the sanction of the Porte and the Powers, has never been formally recognized by them. But Bulgaria has gone on her way in delightful disregard of the powers, minding her own business and thriving astoundingly. The best two years the little country has ever known have been these last two since Ferdinand was seated. Russia in a mark of her very deep disapproval, withdrew her consular representation from Sofia; and the Bulgarians were delighted at the riddance. They already had gotten rid of the Russian officers who formerly had filled the army places, and now for the first time since emancipation from Turkey they were enjoying a respite from outside political intrigues. Austria was now extremely friendly, without being officious and meddlesome. England was thoroughly appreciative, though not to be relied upon for active help. Germany, as Austria’s ally against Russian encroachment, seemed to be in fact a tolerant and not unwilling witness of Bulgaria’s progress.

And so the little state has grown with quick strides since the summer of 1887. It has cemented the union with South Bulgaria – which had been recognized by the Porte and the Powers before Alexander’s abdication – and has begun to tie its territory together with railroads for purposes strategic and commercial. It completed the link of road necessary to establish the international line to Constantinople, and it quietly but forcibly took possession of the part that had been built by others in East Roumelia. I found the Bulgarian government last summer building the Jamboli-Bourgas line, to improve connections with the Black sea ports. The whole population were turning out and giving their labor for excavation and grading, with army regiments also helping. By this splendid spirit of patriotic co-operation on the part of all the people, Bulgaria is acquiring public works which otherwise could not be built; for as yet her credit in the money market has scarcely been established. What more noble sight has the past year witnessed than that of these brave Bulgarian peasants, building themselves a system of state railways by the labor of their own hands, — each man and boy gladly giving five days of hard work? It was a spectacle that stirred my unqualified admiration, and strengthened my already strong faith in the future of these determined people, who help themselves, asking no odds.

Mr. O’Conor, the accomplished consul-general and diplomatic agent who represents England at Sofia (the United states has no representative there), told me that it was quite impossible to get an errand-boy to serve the consulate through school hours, so eager are all the Bulgarian lads to obtain an education. This young principality, just escaped from its centuries of practical slavery under Turkish task-masters, now maintains a system of free public schools with compulsory attendance. A school of the gymnasium rank, which it established several years ago, now has been raised to the dignity of a national university. Private initiative is necessarily weak in these young and undeveloped countries, whether in matters of industry or of culture; and the state does not shrink from undertaking any thing. The people use the state as their only effective agency for the promotion of civilization. How under the circumstances they could do otherwise or why they should desire to do otherwise, let the laissez-faire economist answer if he can. To the theorist who would object that dependence upon the state may lessen the spirit of self-help in these simple Bulgarian people, I can only point to the spectacle of the assembled peasants working side by side with the army sappers, under direction of the army engineers, building their own railroad and never once suspecting that the state was any thing else but themselves organized for their own progress and civilization.

The new capital of this new principality is in a curious process of transition. Ten years ago it was a big, dirty village of eight or ten thousand peasant farmers, lying on the flat plain with a noble mountain rising behind it and with the level fields stretching off in three directions. Like all the Bulgarian towns, it had its environing zone of common lands, where every villager pastured his cows, — these village lands having an origin dating probably from the earliest period of Bulgarian occupation, and having been confirmed to the villages by the Hungarian and afterward by the Turkish conquerors. Out of this squalid condition – that of the semi-Asiatic, semi-Slavonic pastoral, and farming town at its worst estate – is evolving a modern European municipality. The rapidity of the change interested me extremely. The inhabitants of Sofia now claim for it 35,000 people. A new town has been laid out by French engineers, with broad and regular streets, and a large amount of creditable building has been accomplished. The Bulgarians love the land and have the strongest instinct of ownership; and as in the old village every man, no matter how poor, owned his own hut and its narrow bit of ground, and had his cow and perhaps his yoke of oxen, so now every man in the new Sofia owns his own house, as a matter of course. The central establishments of the young government have brought to Sofia the brightest men in the Bulgarian race. The public service absorbs the education and talent of the young country. I found the Robert College graduates, with their superior training, occupying judgeships and high administrative posts. The government has erected a series of respectable buildings for the housing of the prince, the National assembly, the university, the public printing bureau, the law courts, and the various administrative departments. While I was in Sofia an arrangement was concluded by which the municipality obtained a moderate foreign loan for the making of public improvements, — for water-works, gas works, paving, and the like. It is interesting to note the fact that the rapid growth of the town has led to no speculation in lots. The outlying land belongs to the municipality, and when there is a demand for building room, the city council sells what is required. Nobody buys except to improve and occupy.

Marvelous is the rapidity with which the evidences of Mohammedan life and rule are disappearing, even in this brief period of scarcely more than a decade. Thirty percent of the population of Bulgaria was Mohammedan 10 years ago. These people have not apostatized, but they are somehow vanishing. In the National Assembly, there are perhaps six or eight Mohammedans. The Turkish farmers were and are a very industrious, decent people, and they were not much, if any, better treated under the old order of things than were their Bulgarian neighbors. Religious prejudice, however, makes a free and Christian Bulgaria distasteful to them, and they gradually move nearer Constantinople. The years of war and disturbance, of course, occasioned a good deal of population shifting. The mosques were, as a rule, more showy than substantial, and their disappearance from the landscape of the new and free Bulgaria is like the vanishing of the unreal architecture of dreams, or like that of ice-palaces in the spring sunshine.

The Bulgarians take with remarkable readiness to representative government. Their National Assembly, with a single house, is elected by universal manhood suffrage from the two Bulgarias, on the basis of a member for every ten thousand people. The population is about three millions. The Bulgarians in Macedonia and other adjoining districts are at least a million more. If the normal development of the Balkan States can be secured, in the presence of powerful and selfish neighbors, the greater part of Macedonia will some day go to Bulgaria.

Of the Bulgarian church – Greek orthodox in theology and ritual, formerly dependent upon the metropolitan bishop of Constantinople as primate, but now organized as a national church detached from its old connections – my space permits but a word. It is thoroughly patriotic, is inseparably identified with the nation in the popular mind, and is more valuable politically as a race bond, than religiously as a spiritual and moral teacher. The value of American missionary work in Bulgaria must be realized chiefly in its reaction upon popular education, upon the qualifications of the priesthood, and upon the religious vitality of the national church. The thoughtful politicians admit the religious superiority of the missionary teaching, but deplore the possibly divisive effects of their attempts at the organization of new churches.

What, with enemies on every hand, or at least with powerful and unscrupulous neighbors determined to control the future of the Balkan peninsula, is the outlook for ambitious young Bulgaria? At times it appears very dark and sad. But I am not inclined to accept the views of the pessimists. While I cannot see how Russia is to be prevented from sweeping the whole Balkan region before her when she determines to do so, I also remember the age in which we live and the potency of the new race consciousness that has sprung into being, among so many European peoples. I do not see how it can be possible to undo the civilizing work that has been wrought in Bulgaria since 1876, or how the proud young Balkan States could be reduced to the position of Russian provinces, deprived of their representation, of their free presses, of their universal education, and of all their new treasures. Taken into Russia on such terms, they would tear the Russian Empire to pieces. Modern freedom once won is not so easily lost. The moral forces of our day have a power beyond brute compulsion. The Bulgarians perceive this fact; and while they are drilling every mother’s son to arms almost from the cradle, in preparation for defense, they are relying most upon the strength that lies in the moral and educational forces which they are straining every nerve to develop in their people.

Notes:

- Slavonic(sla von´ic) Pertaining to the Sclavi, an ancient people living in that part of Austria and Turkey which lies between the rivers Save and Drave. The term now applied particularly to the language spoken in Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, Bohemia, etc. It is also written Sclavonic.

- The Greek Church “includes the church within the Ottoman Empire subject to the Patriarch of Constantinople, the church in the kingdom of Greece, and the Russo-Greek church. It formally separated from the Roman Church in 1054. They dissent from the doctrine that the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father and Son (Filioque), reject the papal claims to supremacy, and administer the full eucharist to the laity.” In other respects they agree with the Romanists. The Greek Church has been the established church of Russia since the time of the conversion to Christianity of king Vladimir the Great, 988. The reports of the magnificence and impressiveness of the ritual of the church of St. Sophia at Constantinople, as made by his ambassadors, led him to decide in its favor over the Romish Church.

- Robert College. This American college was named from its founder, Christopher R. Robert (1802-1878), a merchant of New York. During his life-time he gave to this institution $296,000, and left it in his will $125,000, besides real estate valued at $40,000.

- The terrible war of 1877. The Russo-Turkish War. Russia, Germany, Austria, and France demanded of Turkey a constitution and guaranties for the benefit of the oppressed subjects in the provinces of its empire. These Turkey refused to grant. Russia then allowed her subjects to render aid to revolted provinces, and the war between the two powers began in April, and lasted until the battle of Plevna, December 10 of the same year, when the Turks were obliged to surrender.

- The Great Powers. “There were in Europe after the overthrow of Napoleon in 1815, five monarchies recognized as the great powers – namely France, Austria, Great Britain, Russia, and Prussia, to which, in 1859, the kingdom of Italy was added. The victories of the Prussians in 1866 And 1870 have so prostrated the armies of Austria and France that there now remain in Europe only two first-rate powers, Russia and Prussia (or Germany), and the balance of power is supposed to be destroyed, for if these two should form an offensive alliance they would be a match for all the other powers on the continent.” – Johnson’s Cyclopaedia.

- Congress of Berlin. This was held from June 13 to July 13, 1878. England, Austria, and Germany, were anxious to prevent Russia from keeping the great advantages she had gained from the war, fearing the balance of power among the great nations would be destroyed.

- Autonomous. (Au-ton´o-mous.) A word derived from the Greek language, meaning having the right of self-government.

- The Porte. The Turkish Empire, officially called the Sublime Porte. The principal gate leading to the palace of the Sultan is called the Sublime Porte (gate), and from this the name came to be applied to his court and then to his government.

- Hegemony. (He-jem´o-ny.) A Greek derivation meaning leadership.

- Autocracy. (Au-toc´ra-cy.) Also a Greek derivative meaning independent power. It is synonymous with autonomy.

- Hesse Darmstadt. This, the old form of the name, has been shortened to simply the first part of the compound, Hesse (hess). It is a state of Germany lying between 49˚ and 51˚ of north latitude and 7˚ and 10˚ of east longitude. T is a constitutional monarchy whose sovereign has the title of Grand Duke.

- Droschka. Written also drosky. “A peculiar kind of low four-wheeled carriage, without a top, consisting of a long, narrow bench on which the passengers ride as on a saddle, with their feet reaching nearly to the ground.”

- Laissez-faire. (Lās-sā-fair.) A French expression meaning let alone; suffer to have its own way. See Ely’s “Political Economy,” pp. 108 and 125.