An editorial by W.T. Stead (The Northern Echo, June 24, 1876), challenging England’s foreign policy concerning the Ottoman Empire and her disaffected provinces.

It will be bad news for England if, while the respite it has procured for Turkey endures, the smouldering sparks of rebellion sown broadcast throughout the Empire should suddenly blaze up, and bring to pass a general conflagration. We shall not be able to plead that there were no warnings of such an eventuality.

It will be bad news for England if, while the respite it has procured for Turkey endures, the smouldering sparks of rebellion sown broadcast throughout the Empire should suddenly blaze up, and bring to pass a general conflagration. We shall not be able to plead that there were no warnings of such an eventuality.

It is true that we have Ministerial cries of “Peace, peace;” but the telegraph contradicts them, and a crowd of witnesses attest the contrary. Never since the Herzogovinese took up arms to avenge their wrongs and enforce redress has the aspect of affairs been so ominous. These rebels are still in the field. Servia and Montenegro are but waiting for permission from their patron, Russia, to raise the standard of revolt. On the fringe of the Empire, if we may so speak, the Slav population is profoundly disquieted. Both men and money are freely offered to assist the insurgents in their attempts to break the chains of an intolerable servitude. While such is the state of things in these localities, a war of extermination is being carried on against the Christians in Bulgaria! Upon the provocation of an insurrection the dimensions of which cannot have been great, a company of Bashi-Bazouks, the off-scourings of Turkish society, which sufficiently describes their character, were let loose upon the people, and never did dogs pursue their game more mercilessly. A wide region of central Bulgaria has been laid waste. The names of thirty-seven villages are given that have been utterly destroyed. Men, women, and children have been ruthlessly murdered. Among the incidents mentioned is the burning of a stable with forty or fifty young women within its walls; and a massacre of innocents, to the number of a hundred, found in a school house. The details are sickening. The total slaughter can only be guessed at. The effect of these atrocities is not pacificatory. As the story becomes known through the disaffected provinces a new impulse will be given to the wish for deliverance. The precise relation of Russia to the Christian subjects of the Sultan is questionable. It may, as suspected, or may not, as it pretends, be fermenting discontent; but this much is certain that it is to Russia that these unhappy people are looking for sympathy and aid. Not to Christian England.

England is Turkey’s friend. The Mussulmans (sic) are going about saying that England will not see the Empire broken up – that, if necessary, it will help to put down insurrections; and that every indication of vigour in this direction, as in Bulgaria, is sure of it warmest approbation. Is all this a delusion? or has England been committed to the course of action thus defined? It is high time that we had an authoritative explanation of our position in relation to Turkey. We are held accountable for the lack of energy displayed in applying the reforms which might give satisfaction to the insurgents. It is to England that Continental critics ascribe the “days of grace” the Treaty Powers have granted; and which, as we learn, are slipping away unimproved, witnessing as they pass a constant aggravation of circumstances, and a heaping up of obstacles to a satisfactory settlement. How and by what means have we been made responsible for these things? The country is too much in the dark respecting transactions that nearly affects its character, and which may be tending to issues it would deeply deplore. If the “sage forbearance” and “patriotic reserve,” as Mr. Disraeli phrases the extreme moderation of the Liberal leaders, continue much longer, we trust some independent member of Parliament will force from ministers a more particular declaration of their policy, and a more detailed statement of their proceedings than they seem disposed to give. The aspect of affairs is decidedly alarming; and it will be little consolation should our fears be fulfilled, that we exhibited a “sage forbearance,” a “patriotic reserve,” while the several atoms of discord were drifting into collision, repressing with exemplary patience and marvellous self-command, the curiosity which might have framed embarrassing questions, but questions that, if asked, and asked in time, might have kept us from trouble, and averted from Europe a sanguinary war.

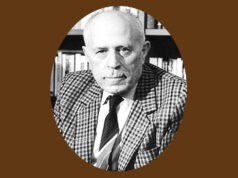

W.T. Stead was a great creative force in British 19th century journalism. He started writing for the fledgling Northern Echo at its inception in 1870, becoming Editor in 1871 at the tender age of 22. He used the railroads to build the paper into a national publication from its base in Darlington. He became interested in Bulgaria in response to the Turkish atrocities committed there in 1876. In 1880 he became editor of the Pall Mall Gazette and in 1890 founded the internationally successful Review of Reviews.

For more information visit: The W.T. Stead Resource Site .

[ad#Chitika Bulstack 468×250 BIG rectangle]