Were treaties and national borders drawn at the end of the First World War midwives to political tangle in the modern Middle East? Did they delay or advance what was to come? The answer is complex, like the current web of victim /perpetrator accusations, and nearly as opaque.

Were treaties and national borders drawn at the end of the First World War midwives to political tangle in the modern Middle East? Did they delay or advance what was to come? The answer is complex, like the current web of victim /perpetrator accusations, and nearly as opaque.

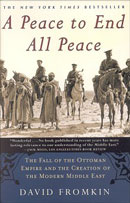

The years 1914-22 were a time when official government accounts seemed motivated by a desire for vindication or self-validation, thus all too often became works of propaganda and even, at times, outright fiction. A stunning example was the fictitious tale of T. E. Lawrence which seeped into world history as fact. David Fromkin’s wealth of data, maps, photos and records, woven together in a brilliant, polyphonic manner, allow one country’s view to counter balance another’s, year by year, engagement after engagement.

Misconceptions and bizarre theories promoted confusion. According to British intelligence, the Young Turks were part of a Jewish German conspiracy which, they said, controlled the Bolshevik regime in Russia. When Afghanis rose up, or Arabs rebelled, or a Turkish region was unsettled or Egyptians refused British absolutism it was seen not as local nationalism, but as Russian conspiracy designed to overthrow benevolent British rule. Such views persisted despite the fact that during the early revolts the Russians were in civil disarray, barely able to cohere themselves, let alone foment wide spread anarchy elsewhere.

The book describes the crumble and decay of the Ottoman Empire, clarifying the process which shaped the modern Middle East. In particular, it reveals the political machinations of the Great powers, the greed and fear which prompted many of Europe’s acts. During this sunset of the Turkish and British colonial eras exposed attitudes which distress a modern sensibility, including feelings of superiority leading to entitlement, Europeans repaid their cronies through land grants for material sacrifices during the war, complaisance with exploitation of native resources, and certainty that, “we know better than (nationals) do.” As 21st century Europeans and Americans, we’ve advanced beyond mere patriarchal slant… or have we?

Balkan and related histories appear, also. Bulgaria’s rivalry with Greece and Rumania made an early treaty joining with France and Britain against Germany unfeasible, yet Bulgaria might join an attack on Turkey. As it turns out, Bulgaria did not – instead she entered the war in 1916 on the side of Germany and Turkey. In October 1918, on the verge of rebellion or defeat, Bulgaria requested an armistice, and its fall cut off Constantinople land routes to Europe. This was a pivotal moment. Other nations soon fell like dominoes, hastening the end of the war.

As a frontier region of the disintegrating Ottoman empire, Macedonia was home to subversive cells. Decades of military failures in the region inspired young Ottoman soldiers to join secret societies, a key stage in the rise of Turkish nationalism. Leaders rose such as Mustapha Kemal, who became Ataturk, a tough minded, lean officer of the Thessaloniki set. Djemal Pasha strengthened Afghani ties to Russia, helped to draft the country’s new constitution. Dardenelle victors such as General Envers Pasha became crusading warriors of the Islamic faith, like the ancient Ghazi, yet Envers died August, 1922 in Burkhara, betraying Turk and Russian friends.

In conclusion, 1918 and the close of the First World War brought “an end to peace.” The West must shoulder significant blame for political problems in the Middle East. Fromkin exposes self interest and fears, particularly that of Britain’s Prime Minister David Lloyd George. He exculpates Woodrow Wilson as weak, ineffectively bleating about the death of colonial expansion. Europe refused to adopt a foreign policy of self determination – should each nation choose a government for itself, without interference from outside powers? President Wilson’s idealistic entreaties fell on deaf European ears.

Life today inside the borders of Jordan and Israel, Iran and Iraq would differ substantially if Europe had moderated its colonial ambitions sooner, and Arab/Israeli relations might be less mired in endless attack and recrimination.

Fromkin’s work can be understood not only as a history, but also as a warning: we should look first to the needs of others before pushing our own agendas.

[ad#Amazon Books bulgarian history, bulgaria]

Citation:

Fromkin, David. A Peace to End All Peace. New York: Henry Holt, 1989.

[ad#Google Adsense Bulstack 468×60 post banner]